[from Lecture 1.1] A real explanation of some aspect of the mind would have to be:

[from Lecture 1.2] A complete explanation of some aspect of the mind would have to be:

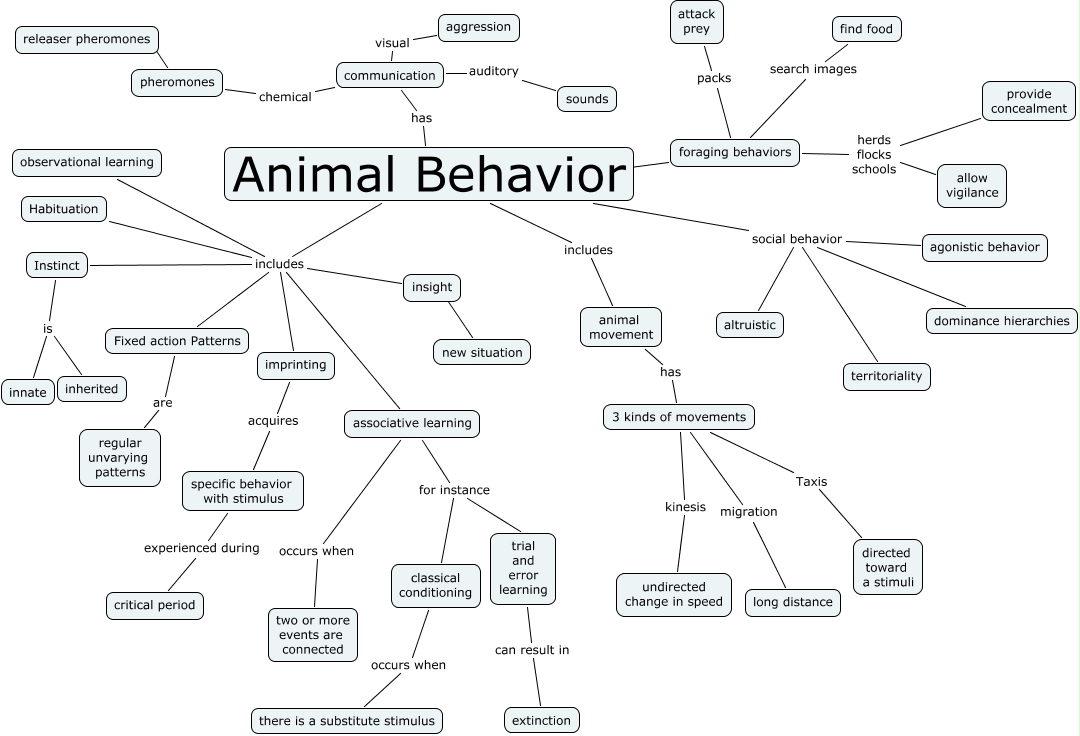

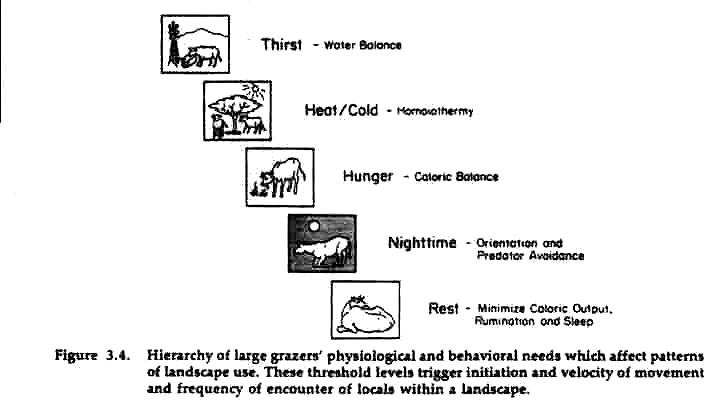

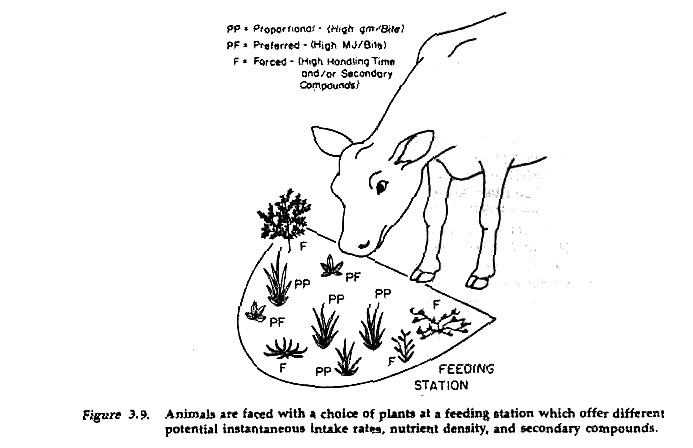

How should we choose what aspects/activities of the mind to study? Ethology — the science of BEHAVIOR — to the rescue.

"Look at our present theories... Look at Hull's system or at the probabilistic models that are multiplying like overexcited paramecia. Although already too complicated for the average psychologist to handle, these theories are not yet adequate to account for the behavior of a rodent on a runway."

— W. K. Estes, Of models and men, American Psychologist 12:609-617 (1957)

In physics — where observations are always given a mathematical formulation — the foundational concern is with quantitative PATTERNS or LAWS, which are to be inferred, by induction, from particulars. (In psychology, Shepard's Law of Generalization, to be discussed in a later week, is a key example; the role of induction in cognition will also be discussed.)

Computational cognitive science requires, in addition to a mathematical theory, an EXPLICIT and EFFECTIVE algorithmic component: a mere statement of "law" (pattern) is not enough. Computational models also aim to explain — productively and quantitatively, not merely verbally — the PARTICULARS OF BEHAVIOR.

"And man is appealed to be guided in his acts, not merely by love, which is always personal, or at the best tribal, but by the perception of his oneness with each human being. In the practice of mutual aid, which we can retrace to the earliest beginnings of evolution, we thus find the positive and undoubted origin of our ethical conceptions; and we can affirm that in the ethical progress of man, mutual support not mutual struggle — has had the leading part. In its wide extension, even at the present time, we also see the best guarantee of a still loftier evolution of our race."

"In the merciless arena of life, we are all subject to the law of the jungle, to ruthless competition and the survival of the fittest – such is the myth that has given rise to a society that has become toxic for our planet and for our and future generations."

"But today the lines are shifting. A growing number of new movements and thinkers are challenging this skewed view of the world and reviving words such as ‘altruism’, ‘cooperation’, ‘kindness’ and ‘solidarity’. A close look at the wide spectrum of living beings reveals that, at all times and in all places, animals, plants, microorganisms and human beings have practised different forms of mutual aid. And those which survive difficult conditions best are not necessarily the strongest, but those which help each other the most."

Video source: A conceptual framework for cross-border impacts of climate change, T. R. Carter et al. (2021). Global Environmental Change 69:102307.

See also: The planetary commons: A new paradigm for safeguarding Earth-regulating systems in the Anthropocene, J. Rockström et al. (2024). Proc. Natl. Acad. Sci. 121(5):e2301531121.

Behavior is much more than

(Some) psychologists knew it all along:

To make real progress towards understanding behavior, one must study ethology and evolutionary ecology.

"The structural unit of the nervous system is in fact a triad, neither of

whose elements has any independent existence. The sensory impression exists

only for the sake of awaking the central process of reflection, and the

central process of reflection exists only for the sake of calling forth the

final act."

Another facepalm is in order (look at the subtitle)...

"What we have is a circuit, not an arc or broken segment of a

circle. [...] The motor response determines the stimulus, just

as truly as sensory stimulus determines movement. Indeed, the

movement is only for the sake of determining the stimulus, of fixing

what kind of a stimulus it is, of interpreting it.

[...] There

is simply a continuously ordered sequence of acts, all adapted in

themselves and in the order of their sequence, to reach a certain

objective end, the reproduction of the species, the preservation of

life, locomotion to a certain place. The end has got thoroughly

organized into the means."

"My main thesis is that conduct originates in the organism itself

and not in the environment in the form of a stimulus. [...]

Perception is the discovery of the suitable stimulus which is often

anticipated imaginally. The appearance of the stimulus is one of the

last events in the expression of impulses in conduct. The stimulus

is not the starting point for behavior."

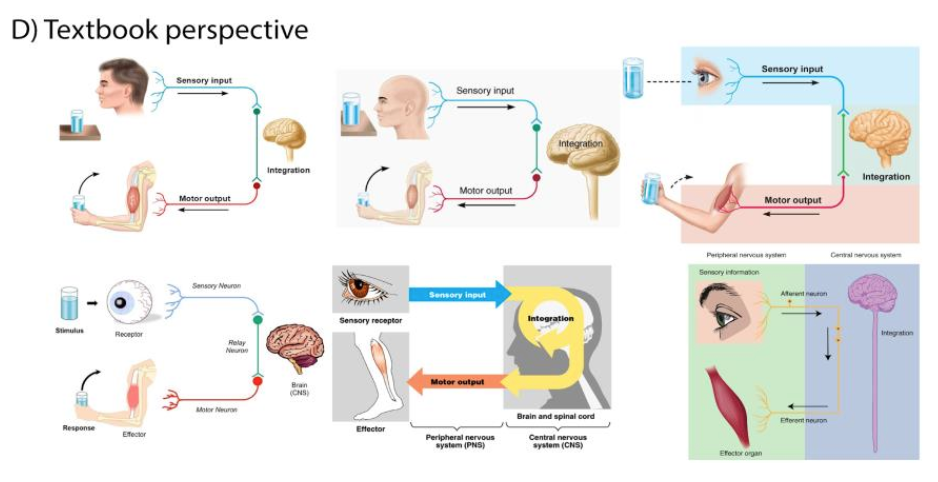

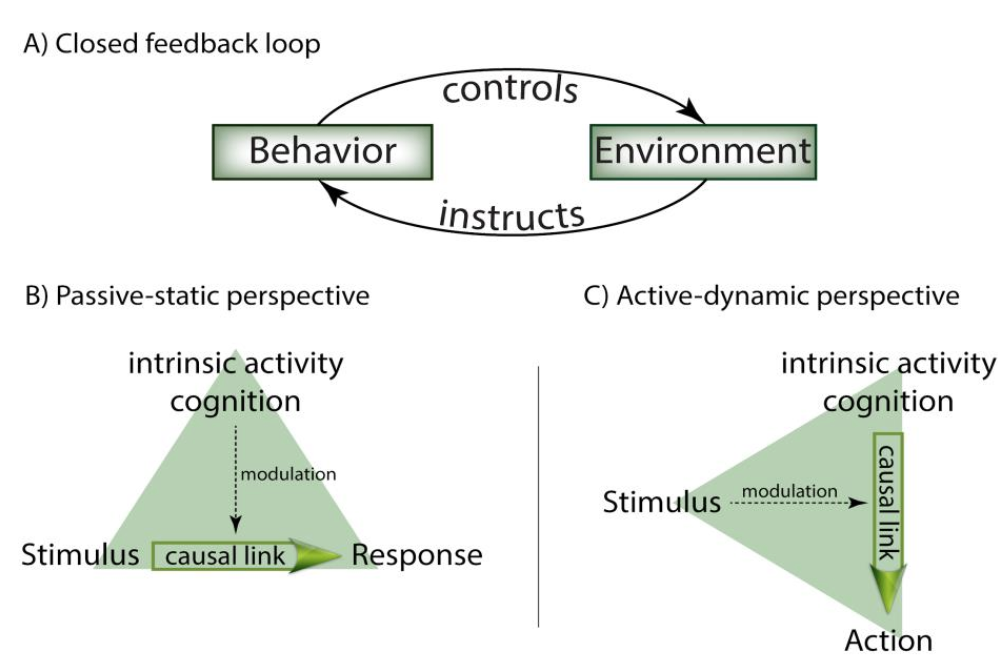

Six arbitrarily selected examples from neuroscience textbooks schematically depicting the passive-static perspective on nervous system function.

"In the second half of the last century, a whole institute (Max Planck Institute of Biological Cybernetics, Tübingen) was founded on the discovery of an input-output behavior, the optomotor response, which for the first time had been described by a mathematical algorithm. Drosophila got introduced to many branches of neuroscience and has made fascinating contributions to these fields. Yet, has any of that spectacular progress revealed how brains work? Rather not; neither in the Tübingen School nor anywhere else. Why? What is the problem with brain research? The problem is the input-output doctrine. It is the wrong dogma, the red herring. The hard-wired reflex, the innate response to a stimulus, is not the essence of brain function, not the basic building block of behavior. Behavior is problem solving. It is part of the evolutionary process. It is fundamentally active."

[from The Beauty of the Network in the Brain and the Origin of the Mind in the Control of Behavior, M. Heisenberg, J. Neurogenetics, 28:389-399, 2014]

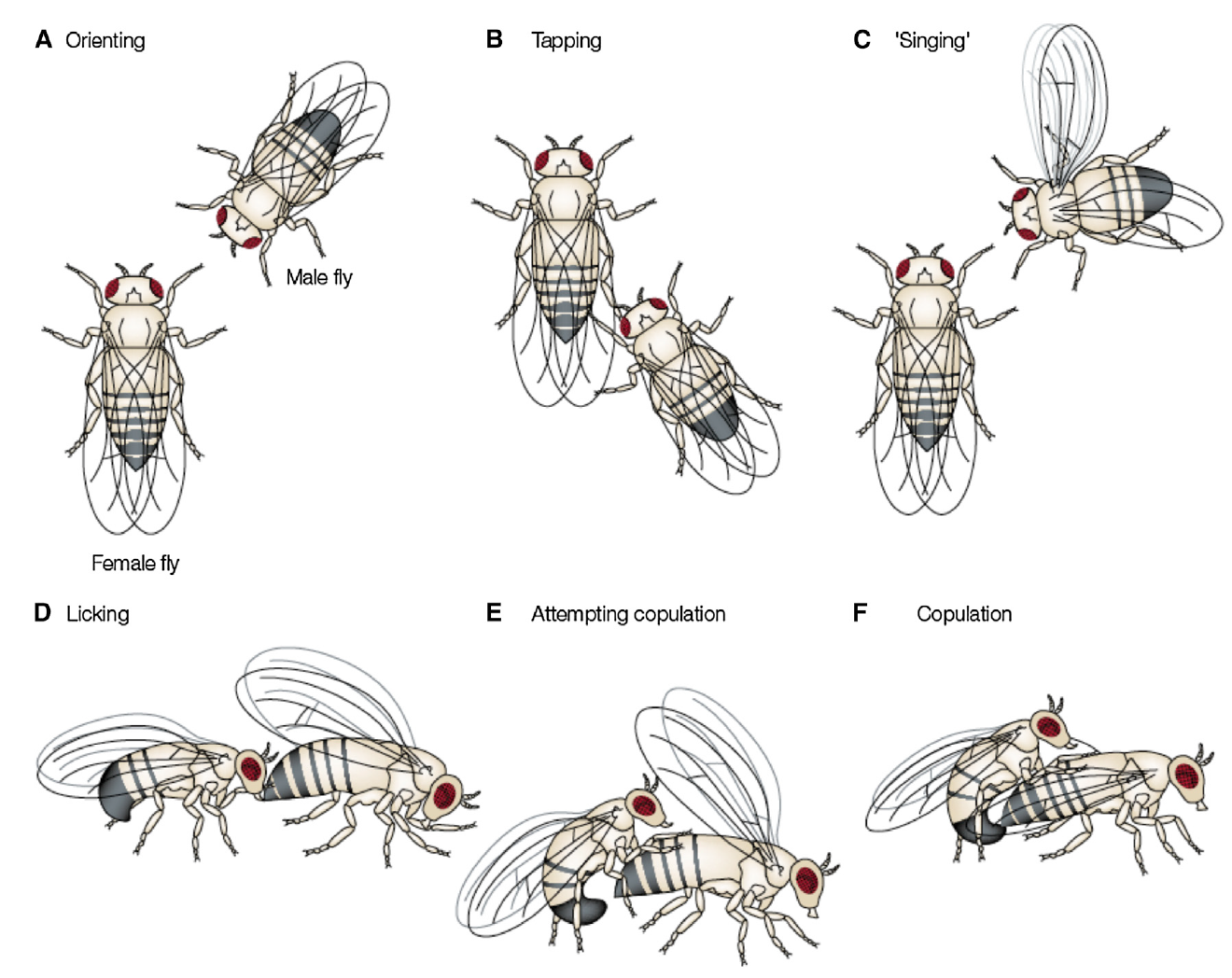

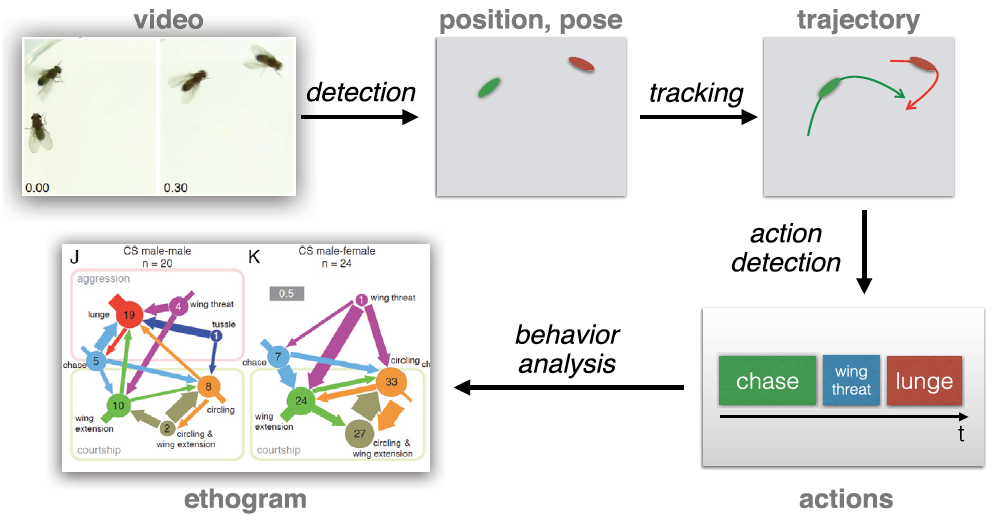

The new field of ‘‘Computational Ethology’’ is made possible by advances in technology, mathematics, and engineering that allow scientists to automate the measurement and the analysis of animal behavior. We explore the opportunities and long-term directions of research in this area.

Toward a Science of Computational Ethology, D. J. Anderson and P. Perona, Neuron 84:18-31 (2014).

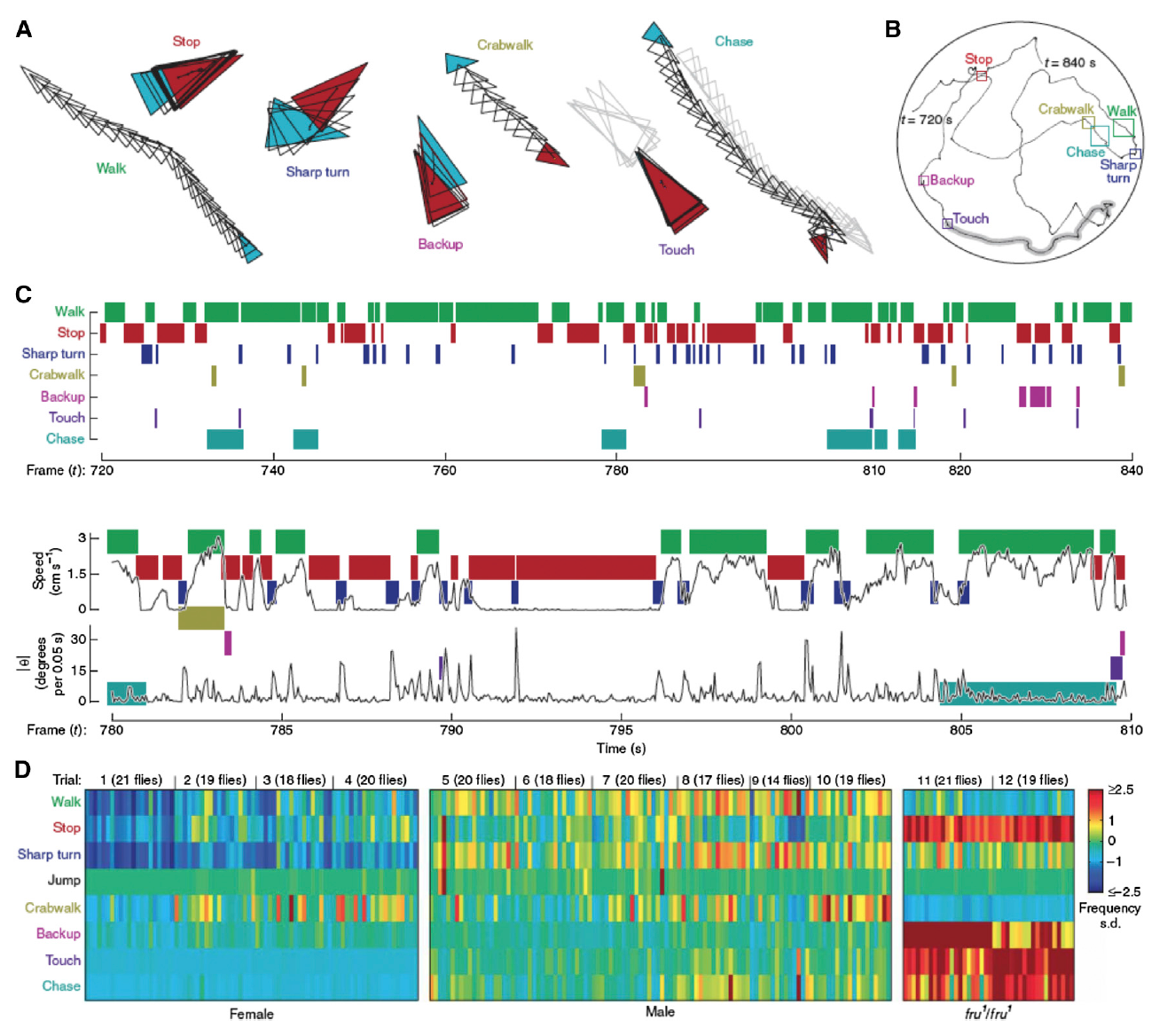

On the right: Summary of steps in the automated analysis of social behavior. Each of the four steps (detection, tracking, action detection, and behavior analysis) requires validation by comparison to manually scored ground truth. The ethogram illustrates different behaviors performed during male-male and male-female social interactions.

Ethograms based on machine vision analysis of multiple flies, for eight different behaviors.

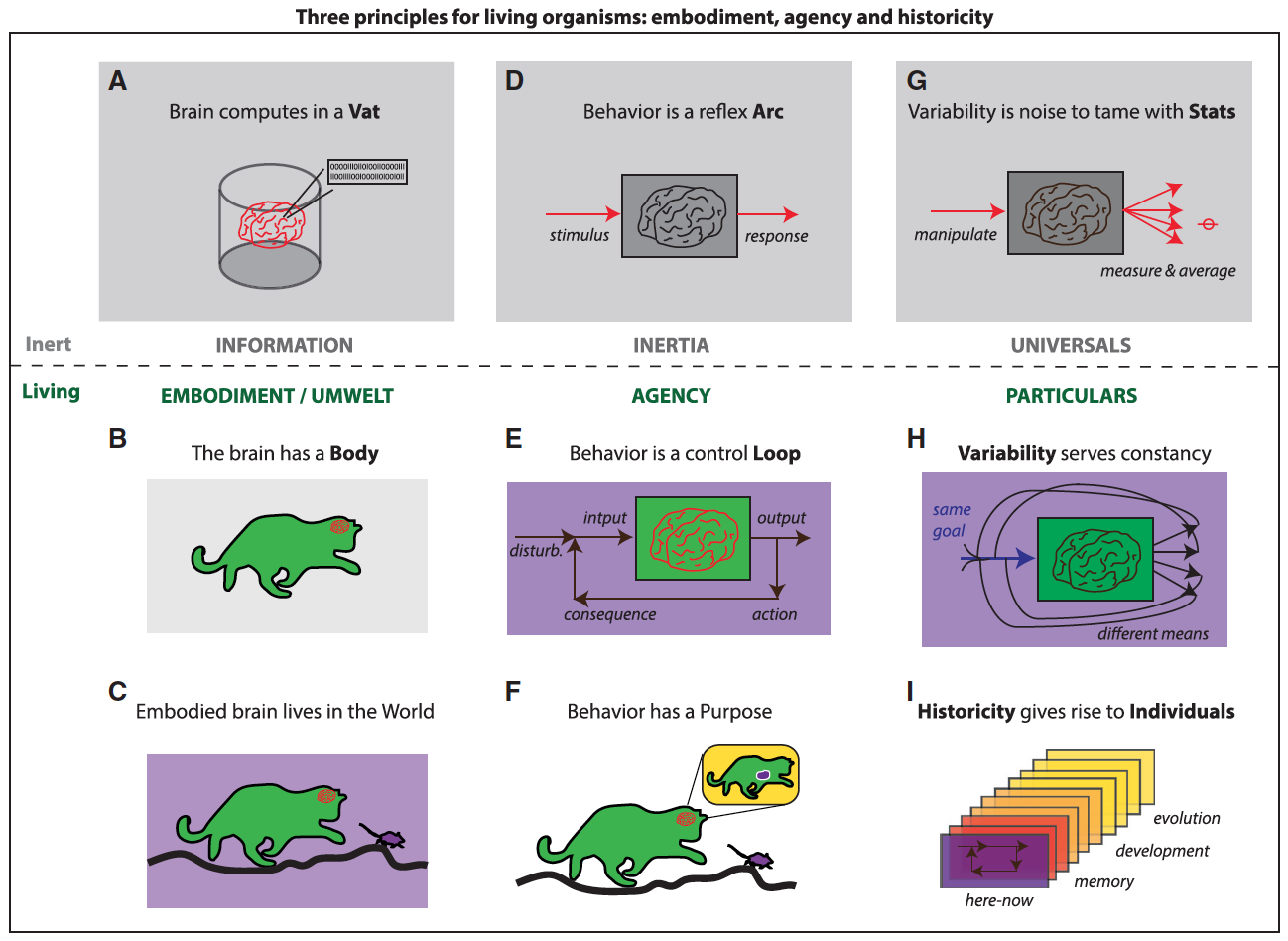

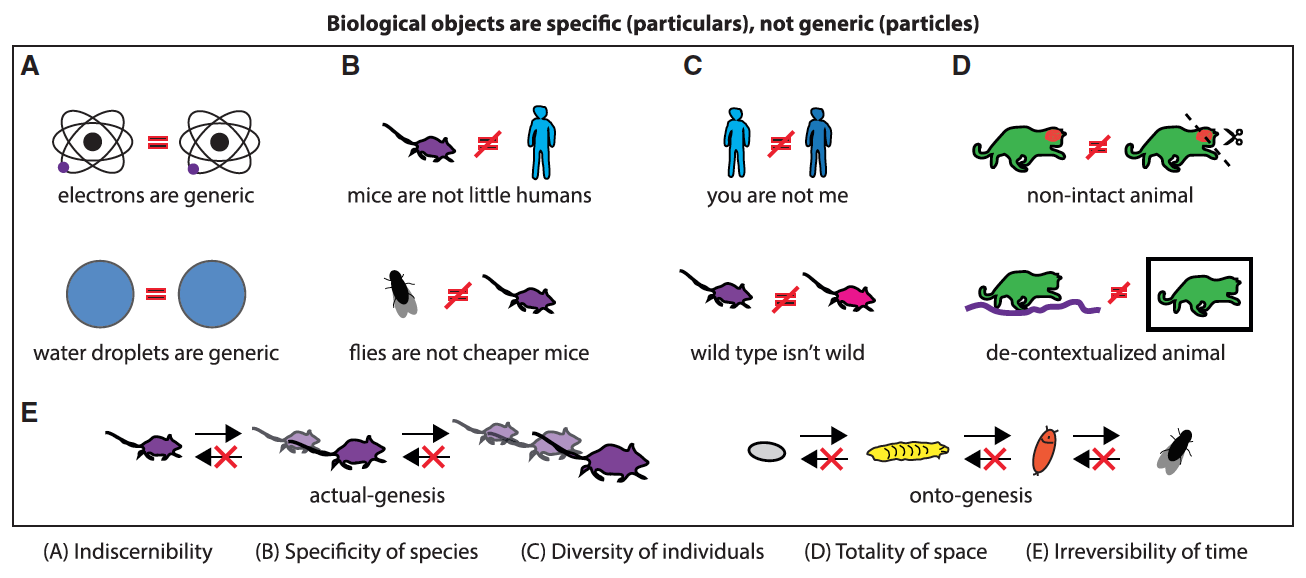

"It is daunting to render the behavior of organisms intelligible without suppressing most, if not all, references to life. When animals are treated as passive stimulus-response, disembodied and identical machines, the life of behavior perishes. Here, we distill three biological principles, spell out their consequences for the study of animal behavior, and illustrate them with various examples from the literature.

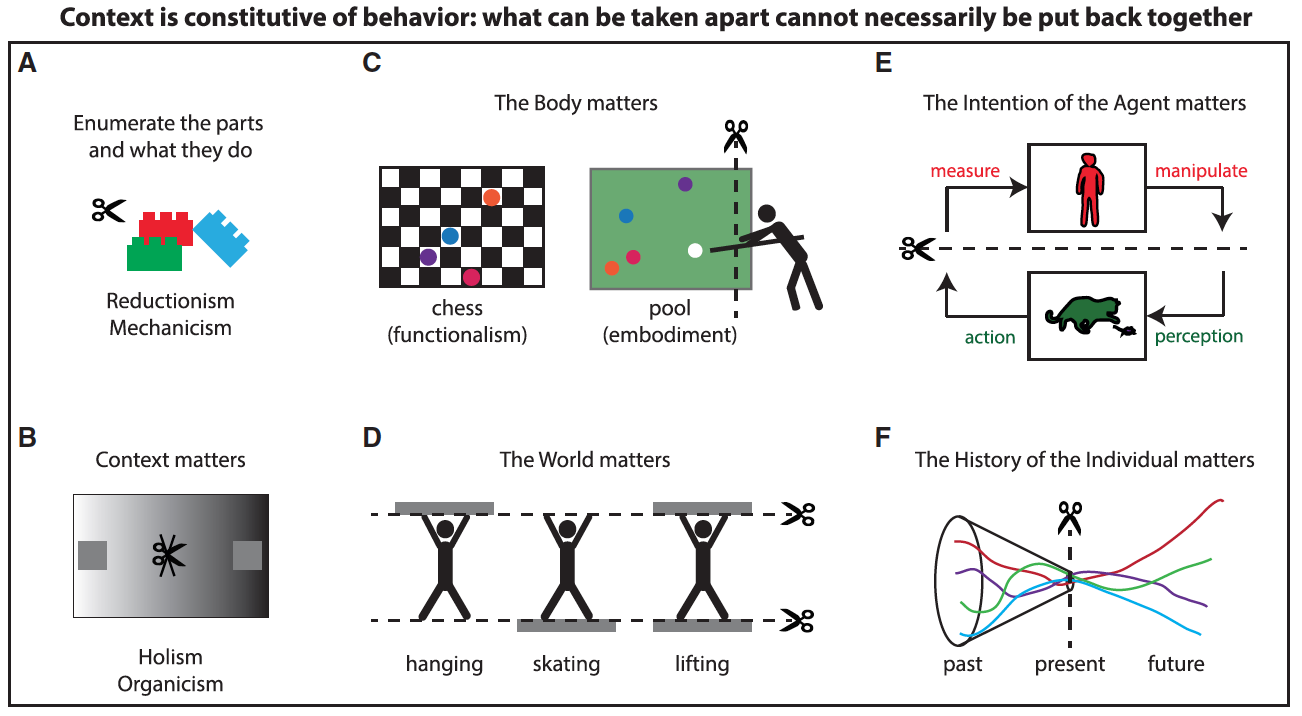

We propose to put behavior back into context, with the brain in a species-typical body and with the animal’s body situated in the world; stamp Newtonian time with nested ontogenetic and phylogenetic processes that give rise to individuals with their own histories; and supplement linear cause-and-effect chains and information processing with circular loops of purpose and meaning. We believe that conceiving behavior in these ways is imperative for neuroscience."

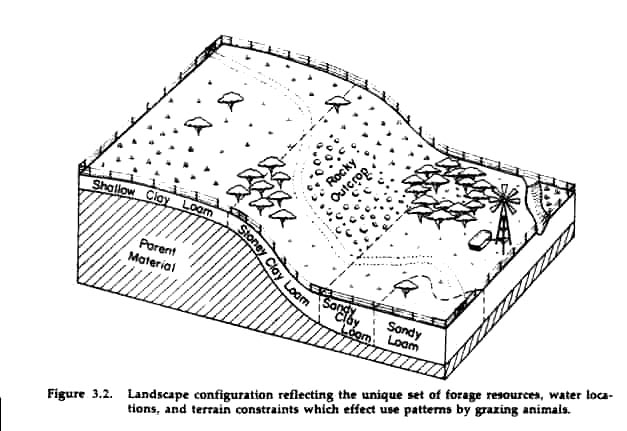

"The three principles are a subset of features arguably unique to life. We claim their necessity to understanding living organisms and reformulate them as fundamental principles in behavior rather than as mere characteristics. The principles are materiality, agency, and historicity. Behaviorally, they account for the constitutive roles of (1) morphology and environment; (2) action-perception closed loops and purpose; and (3) individuality and historical contingencies. These factors make up ‘‘the life of behavior.’’"

"Chimps use sticks to gather honey, termites, and ants from the ground or trees in order to eat them without getting stung, bit, or pinched. We can use this behavior to illustrate how materiality, agency, and historicity contribute to an explanation.

The goal of tool-using in this case is to acquire energy. This goal belongs to a hierarchy of goals: a higher level than having enough energy is the goal of not dying; a level below acquiring energy is the goal of finding a tool and then using it properly, which in turn entails the goal of approaching the potential food source. Levels above answer why; the levels below answer how. Depending on the task (breaking, prodding, or collecting), the stick can be held in various ways, including the precision grip (that is, between any two fingers but without the use of the palm). This illustrates an equifinality; chimps will diverge in the means but converge in the goal. To perform a precision grip requires specific hand biomechanics (e.g., thumbs that rotate around a joint). All Old World primates (and one New World monkey) can perform a precision grip; other animals cannot.

Tool use also requires specialized neural circuitry operating in conjunction with those biomechanics in a goal-directed manner. The precision grip is correlated with extensive cortico-motoneuronal terminations in the ventral horn of the spinal cord, and motor planning and coordination are associated with neocortical areas 2 and 5, which are enlarged in tool-using primates. Finally, tool use is also a learned behavior; young chimpanzees learn by watching older chimpanzees combined with trial and error. Thus, tool use is a behavior bound to the body and brain circuits, and that emerges on evolutionary and developmental timescales."

The ceteris paribus principle (‘‘the same produces the same’’) is inapplicable in experimental biology, since the covert assumption ‘‘all things being equal’’ actually fails.

"In stressing that animals operate under circular causality, one could be tempted to conclude that what we need to do is to map animals to machines. Behavior would then be an engineering problem. Such a view would not grant animals with purpose, however. The life of behavior is circular causality toward a goal.

William James made the distinction beautifully: ‘‘If now we pass from such actions as these to those of living things, we notice a striking difference. Romeo wants Juliet as the filings want the magnet; and if no obstacles intervene he moves towards her by as straight a line as they. But Romeo and Juliet, if a wall be built between them, do not remain idiotically pressing their faces against its opposite sides like the magnet and the filings with the card. Romeo soon finds a circuitous way, by scaling the wall or otherwise, of touching Juliet’s lips directly. With the filings the path is fixed; whether it reaches the end depends on accidents. With the lover it is the end which is fixed, the path may be modified indefinitely’’ (James, 1890, p.7)."

[Beautiful, but irrelevant. Machines can be much more complex than a pile of iron filings. In Shakespeare's story, Romeo is one such machine; Juliet another.]

Walking one evening along a deserted road, Mulla Nasruddin Hodja saw a troop of horsemen rapidly approaching. His imagination started to work; he saw himself captured or robbed or killed and frightened by this thought he bolted, climbed a wall into a graveyard, and lay down in an open grave to hide. Puzzled at his bizzare behaviour, the horsemen – honest travellers – followed him. They found him stretched out, tense, and shaking. “What are you doing in that grave? We saw you run away. Can we help you? Why are you here in this place?” “Just because you can ask a question does not mean that there is a straightforward answer to it,” said Nasruddin, who now realized what had happened. “It all depends upon your viewpoint. If you must know, however, I am here because of you – and you are here because of me!”

Merovingian: You see, there is only one constant, one universal, it is the only real truth: causality. Action. Reaction. Cause and effect.

Morpheus: Everything begins with choice.

Merovingian: No. Wrong. Choice is an illusion, created between those with power, and those without. ... Causality. There is no escape from it, we are forever slaves to it. Our only hope, our only peace is to understand it, to understand the `why.’ `Why’ is what separates us from them, you from me. `Why’ is the only real social power, without it you are powerless.

From Computing the Mind (ch.10, p.464):

FREE WILL is “a philosophical term of art for a particular sort of capacity of rational agents to choose a course of action from among various alternatives”. Upon a close examination, this seemingly simple concept disintegrates into a heap of contradictions, as noted by Voltaire: “Now you receive all your ideas; therefore you receive your wish, you wish therefore necessarily. [. . . ] The will, therefore, is not a faculty that one can call free. The free will is an expression absolutely devoid of sense, and what the scholastics have called will of indifference, that is to say willing without cause, is a chimera unworthy of being combated” (cf. Dennett, 1984, p. 143).

Contrary to the popular misconception, randomness is not a solution to the problem of reconciling free will with physics: I want my decisions to be up to me—not blind chance or implacable fate. In the pursuit of free will, giving up determination in favor of randomness is like inviting the Vandals into the city just to dispose of its tyrant.

Intrigued? Outraged? Want to read more? See chapter 10 of Computing the Mind.

Still intrigued? Insufficiently outraged? There's The Consciousness Revolutions: From Amoeba Awareness to Human Emancipation.

Wait, there's more! My next book, provisionally titled Dialectics of Freedom, is in the works; watch this space!

Last modified: Thu Jan 30 2025 at 08:10:01 EST